Tameem Shaltoni is a New Zealander of Palestinian Arab descent, born in Jordan to a family of Palestinian Arab refugees. Here he writes about a lesser known aspect of ANZAC history.

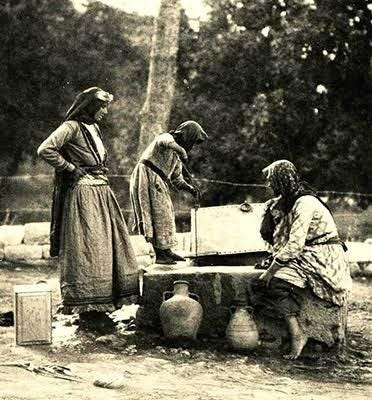

It was a normal Mediterranean autumn day in the usually calm village of Sarafand, except for the audible shouting of villagers and unusual hustle and bustle. Half an hour earlier, a group of Sarafand’s women were fetching water from one of the wells, when a few foreign troopers harassed them; a sight that became too frequent since an entire army division camped next to the village.1

One month earlier, World War One in the Middle East ended. The Allied powers had just defeated the Ottoman Empire, the ANZACs camped near Sarafand in Palestine waiting to be sent home. But Britain was not done with Palestine yet: one year earlier, and culminating an antisemitic belief of Christian Zionists in the British bureaucracy that Jews controlled the world,2 the British government announced on 2 November 1917 its support for the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine (a home to a small Jewish minority at the time) in the hope of enticing the worldwide Jewry to influence Britain’s allies the United States and Russia to commit to WWI and end the 1917 stalemate.

In fact, many ANZAC soldiers who were in Palestine at the time viewed their mission just as that: a biblical mission to redeem the “Holy land” and to “restore the homeland to the one nation left without a homeland” as the sister of one Australian soldier wrote in a letter to her brother.3 It is not hard to imagine what the native population in Palestine, who were not consulted on the war or Britain’s control let alone hearing about the invading army’s intention to give away their own lands, thought of Britain and the ANZACs.

To try to imagine what the ANZACs’ attitude towards the natives in Palestine was, I will quote below the words I found in a 1919 New Zealand newspaper ‘The Colonist’ which reflected how Palestinians (and Arabs) where thought of in the Anglo sphere:

“The whole of Palestine abounds with nomadic tribes of Bedouins, whose mission in life is to murder and steal. Their history down through the ages has been one long story of raping and murder… The Bedouin’s hand is against every man, and no man is his friend. They are a people with two objects in life – to kill and steal. With their little flocks of fat-tailed sheep and goats they move from place to place, as in the time of Abraham. Their various tribes prey one upon the other. The young men steal their wives from the neighboring tribe.”

Back to that autumn day in Sarafand. Upon hearing the news about the soldiers harassing the village’s women at a local water well, a group of young men headed to where the soldiers were reported to hang out and engaged in a scuffle with them. Two days later on 10 December 1918, the ANZACs committed an atrocity: a large group of ANZACs armed with bayonets and clubs surrounded the village then killed up to 120 men of Sarafand. Having killed all the men in the village, and expelled the women and children, the ANZACs burned the village’s houses and orchards, destructed the water wells, and killed the cattle.

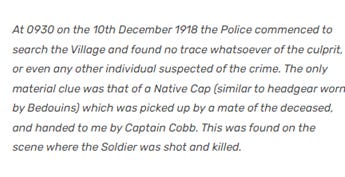

The story of what happened in Sarafand on that day which I wrote above is one of the varying accounts I found written in Arabic as reported by descendants of the atrocity’s survivors. The official ANZAC’s version of the story differs in the background but agrees with the details of the atrocious attack on the village and the bloody outcome of it. According to the ANZAC’s account, Leslie Lowry a 21-year-old New Zealander trooper was found shot and dead outside of his tent and next to him there was a skullcap and barefoot tracks leading towards Sarafand. A military court of inquiry dismissed the available evidence (a copy of the police report is below), but two hundred of the soldiers (mostly New Zealanders and Australians) weren’t satisfied and therefore decided to take matters into own hands. The rest of the story is the same. No one was ever held responsible, although some reparation was later paid by New Zealand and Australia to Britain to re-build the village.

Regardless of the story’s true background (it could be a combination of both narratives), it was with no doubt a horrifying atrocity that must have devastated the village and its hundreds of families and terrorised the surrounding villages and towns. As I write these words, I think of the village’s children who lost their fathers and the women who might have witnessed the killing of their husbands and brothers from afar, and it is heartbreaking.

As it is the case with many events in Palestine’s history, the Sarafand massacre by the ANZAC is not well known in New Zealand. There is very little about the massacre in New Zealand’s history resources. Last month I ran a Twitter poll and I found that 77% out of the 253 respondents knew nothing about Sarafand massacre. Now here the thing, my audience on Twitter (and consequently the vast majority of the 253 respondents) are whom I consider more informed about Palestine than the average New Zealander, given that I am Palestinian and I constantly tweet about Palestine. I suspect the lack of knowledge of the Sarafand massacre at a national level is even more than my Twitter’s poll of 77%.

Sarafand massacre is only one dark episode of [the ANZAC’s and] New Zealand’s history, along with many other atrocities including those committed against New Zealand’s indigenous Māori people as part of the New Zealand Wars, which we as a nation need to do better to learn about and reflect on. Learning about our history, be it here in Aotearoa New Zealand or overseas such as in Palestine, makes it easier to understand the present and where people are coming from.

I chose to write this article to coincide with the ‘ANZAC Day’ this year, to raise awareness of a side of ANZAC history which is not known to many. I am dedicating this ANZAC day to commemorate the 120 Palestinians of Sarafand, whom were killed by ANZACs. I am hoping one day the Aotearoa New Zealand government will make an apology to the descendants of Sarafand’s survivors.

While researching the Sarafand massacre, I came across various articles about it published in English which didn’t include the survivor Palestinians’ narrative and neither the context of Balfour declaration. I made a point in this essay to incorporate the wider context of Britain’s intentions of colonising Palestine and go against the native population’s right to self-determination, and the Palestinian narrative which is present in online Arabic sources.

If you found my writing helpful and learned a thing or two, you are welcome to make a financial contribution through my author profile https://ko-fi.com/tameem to help me in dedicating more time to writing and researching. Palestinian voices are virtually absent in mainstream and influential social media spaces in Aotearoa New Zealand, and through my writing I am aiming to fill the gap and lack of knowledge about Palestine which is compounded by the lack of Palestinian perspective in history curriculum. I write about my own experiences and perspective as a Palestinian, and I also share news from Palestine.

Dr. Sharif Hammad, ‘Sarafand Al-‘amar’

Tom Segev, ‘One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate’

Ilana Bet-El, ‘A Soldier’s Pilgrimage: Jerusalem 1918’