We are all collateral (part II)

Patching the system: public service journalism as pillar of social self-defence against information warfare

Emanuel Stoakes is a New Zealand based journalist who has written for The Guardian, The Washington Post, The New York Times and many other publications. He is currently pursuing his Masters degree at the University of Canterbury, where his research focuses on the role that journalism can play in protecting democracies from information warfare. See Part 1 of this series.

On a nondescript Autumn afternoon four years ago, a lone gunman walked through the gates of an unsecured house of worship in Christchurch and attacked defenceless congregants gathered for Friday prayer. This act of cowardly sadism was live-streamed and subsequently shared around the world, viewed by millions within days.

The spectacle of cruelty perpetrated on March 15, 2019, marked a grim milestone for Aotearoa. Never before had modern media technology been used to bend the international spotlight to an act of political murder on our soil. Never before had the entire machinery of New Zealand media been so tested in its collective response.

For all the horror, the fourth estate - often criticised for its lapses into irresponsibility and sensationalism - generally rose to the ethical challenge of covering the event, largely sidestepping the perpetrator’s attempts to weaponise media attention for his political cause.

The mass murderer of that day, who will not be named here, sought to use media attention to attract attention to both his deed and the cause he hoped to promote through the shocking nature of his crimes. Most major outlets in New Zealand recognised this and acted to limit their instrumentalisation. There seemed to have been a spontaneous consensus in editorial-decision making to act in a way that minimised attention for the killer and his political objectives, with a focus instead on the victims.

The terrorist faded into the background. As one member of Christchurch’s Muslim community reflected in the days after the attack: “he is alone, everyone else is together.”

Mourners gathering at Deans Ave., Otautahi Christchurch, in the days after the terror attack. Photo taken by the author.

A tribute to the victims of the Mosque attacks, laid beside the Botanic Gardens, Otautahi Christchurch. Photograph by the author.

The unplanned kaupapa that the event inspired suggests that our islands are relatively well-placed to demonstrate social unity in the face of overt malicious assaults.

But what about covert assaults, such as pernicious, sustained state-sponsored campaigns that are designed to have a cumulative effect, which are difficult to detect and which seek to something similar to the Christchurch terrorist - the ‘acceleration’ of societal fracture- but through vectors like social media?

Conceptualising the problem

Above is an outline of a suite of practices that have been collectively bracketed as ‘information warfare,’ ‘active measures and ‘cognitive warfare’. The connecting principle between each of these phenomena is the intentional manipulation of public opinion by hostile actors to interfere, and weaken, the societies of their targets, to precondition them for further escalations that will sow discord and chaos, with the costs often being borne most severely by vulnerable people.

The aim is to achieve strategic gains for adversaries short of war. A classic example of this in recent years is the Russian campaign against the 2016 US election.

While it is almost certainly an overstatement to say that the Kremlin somehow hoodwinked voters to elect the insurgent Republican candidate, Donald Trump, the attack on the American poll was nonetheless sophisticated, comprehensive, multimodal, hugely ambitious - and highly successful in achieving its core aims: fomenting chaos, mutual suspicion and social unrest, while nudging some undecided voters to either feel demoralised and unlikely to cast their ballots, or to motivate others to do so, but for Russia’s preferred candidate. It fed off existing discontent to mobilise narratives, disinformation and anxieties that could be appropriated further at a later date.

Scholar Lennhart Maschmeyer proposed that Russia’s 2016 election interference campaign against the US represented an attempt to ‘hack democracy’ by subverting and repurposing its processes, much like a sophisticated hacker might seek to do with an operating system. While cold war style subversion sought to exploit entry-points in society, this targeted “sociotechnical” structures- namely, digital communicative spaces used by millions of people, who could be profiled and micro-targeted.

The process that took place is described by Maschmeyer as establishing ‘reverse structural power’, through cyber offensives deigned to “exploit vulnerabilities in Information Communications Technologies (ICTs) and the way they are used in modern societies” so as to produce “outcomes neither expected nor intended by their designers or users.” This method of attack has the advantage of creating dilemmas for the targeted democracy; to disagree with a groundswell of vituperative, if misinformed, public opinion is inimical to opportunist political discourse, yet to normalise causes greater social harm. Absent nuanced and careful responses, the problem magnifies itself through the reflexes of self-interested political actors and a partisan commentariat.

At the end of the Trump term, a culmination of sorts - by design or coincidence- occurred: the 2020 election was declared a fraud, and the idea that voters could believe in American democracy, as a whole, was discredited on the basis of a lie. The very symbol of US democracy was attacked.

Image of a gallows constructed outside of the US Capitol on January 6, 2020. Photo by Tyler Merbler (Flickr) https://www.flickr.com/people/37527185@N05 Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

In Aotearoa New Zealand we have not yet experienced information and cyber warfare, amounting to structural societal assaults, on anything like this scale. But we should not be complacent. As a country relatively under-exposed to such things, if a comparatively small, yet similarly comprehensive, attack on our democracy occurred, would we be able to detect and expose it before it did significant damage?

Hints of the themes of 2016 were seen during the pandemic. The meta-narrative of anti-vaxx disinformation spreaders centred around the belief in elite conspiracies, the bankruptcy of the social contract, constructing false stories that resonated with the very real alienation from authority that many people feel.

Whether or not this was influenced by external forces is, in a sense, beside the point, what matters is that we have a vulnerability that needs attention; especially since worse may be yet to come.

What to do?

As I have argued before, the media has a key role to play in enhancing democratic security by responding effectively to the threat of cyber-enabled information warfare and to “sound the social alarm”, in the words of Sociologist Ulrich Beck, on the risk environments that our society inhabits.

It would be conceited in the extreme to dismiss the accumulated knowledge of professional journalists as unfit for purpose in the face of these new challenges. In fact, to this writer at least, texts on standards and ethics such as those provided by Reuters, prompt an opposite conclusion: that the best practices of media provide a firm foundation for principled journalists to produce balanced work that nonetheless holds power to account. However, not all media behave according to best practices.

In Noam Chomsky and Edward Hermann’s 1988 work “Manufacturing Consent”, often cited by critics of journalism, the authors offer a persuasive model of how the media can provide at times excellent and thorough reporting on some issues and entirely neglect others. The net result, they propose, is that mainstream press can become, in effect, propagandistic - not because someone is issuing edicts from above, but for structural reasons, the pressures of profit-seeking and editorial filtering.

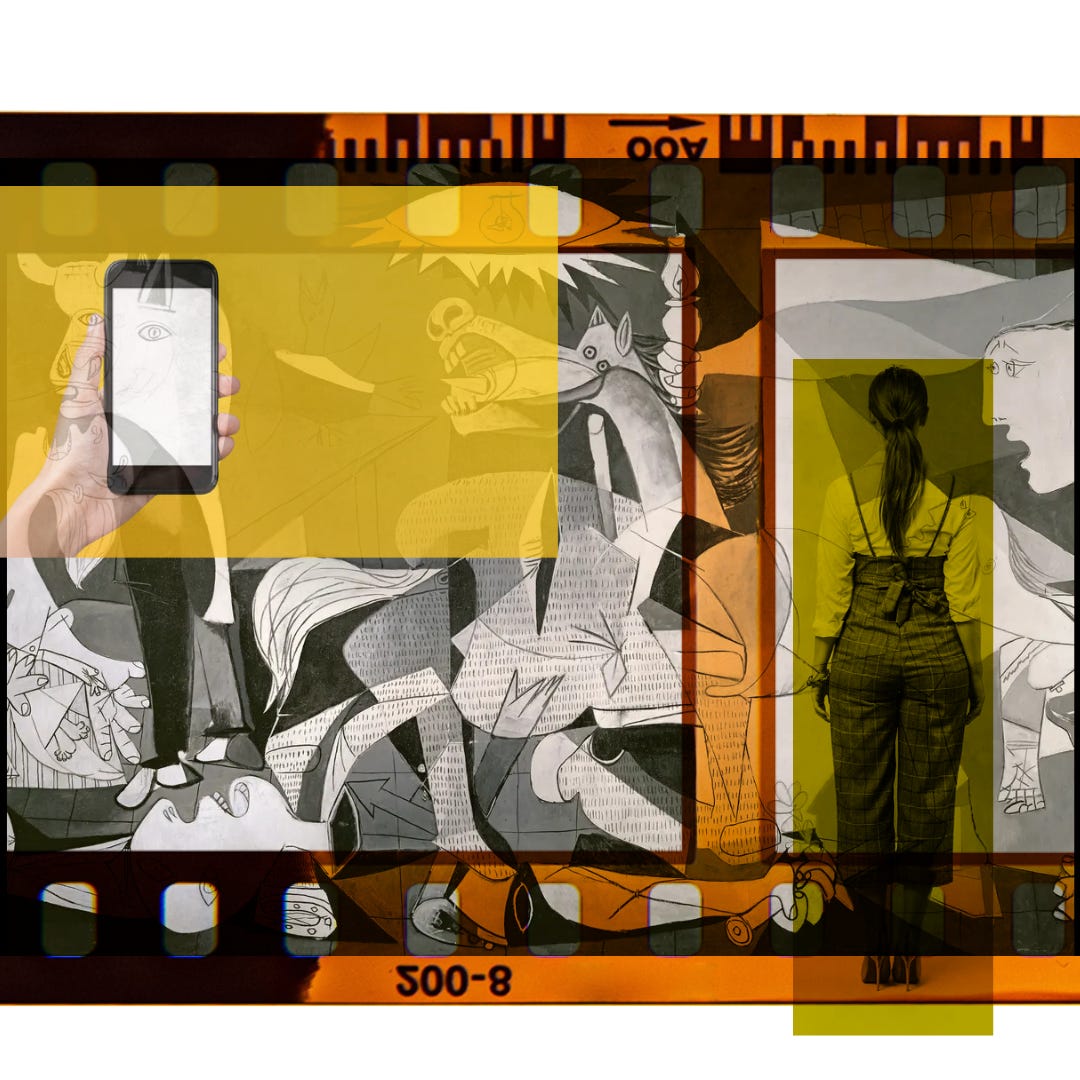

Embed:

This is where, I contend, much of the problem lies. Not that journalism can’t do its job well, but that, because of filtering effects and blindspots, it doesn’t always serve the public interest as fully as it could.

This situation is magnified by the money problem that the media industry faces. One of the central questions that has bedevilled journalistic ethics is the tension between wanting to tell stories that matter, in a nuanced and professional manner, while balancing this against market pressures - the capitalist environment - so that publications remain competitive. The inherent contradiction between journalism as a public service and journalism as a business, where sensational ‘clickbait’ stories generate more money than responsible ones, and, more importantly, occupy the space available to other issues, continues to haunt the industry.

In theory, the answer to the above seems relatively simple: liberating journalists from the pressures of competitive profit-seeking, to free up its capacity for social usefulness, redirecting resources to public-service oriented projects; dedicated coverage of injustices, holding power to account more fully, both at home and against those who seek to harm society from overseas.

But all this takes money, time and costly expertise that are in short supply, as social media has sucked up much of the advertising revenue that print outlets used to depend on for their survival - leading to a protracted funding crisis for the media sector. The money has to come from somewhere, as does the technical knowledge required to identify, disprove and deconstruct viral falsehoods that emerge from alternative information sources.

Popperian method and its implications

Before we attend to the resourcing problem, the problem of disinformation as a general phenomenon should be considered. Are there heuristics that can be brought to bear on the challenge that the average news consumer can apply?

The Philosopher Karl Popper, who wrote his most famous work, The Open Society and its Enemies while he was at Christchurch’s Canterbury University during the Second World War, provides some ideas from which we may be able to draw some inspiration.

Popper’s continuing significance, many years later after the publication of this book, lies in the relevance of his ideas to new social phenomena that echo old problems. In his day, the far-right were not only a meaningful communicative force in parts of the information sphere, but dominated a powerful nation that threatened to overtake much of the world. He was concerned about how to protect democratic values in an age when its survival seemed far more imperilled than it does now.

In ‘The Open Society,' Popper presented a vigorous defence of the idea of a rationally organised society where decisions can be made through rigorous debate and the intelligent application of reliable critical methods to questions of policy and public interest, where the democratic system is moved to correct itself on the basis of extensive public criticism, of trials and proofs, a process in which all communities have a stake and a voice.

At the heart of his social vision was the importance of mobilising, not partisan passion, but epistemological clarity: to provide a methodological basis for assessing truth claims. This is applicable to the problem of how information consumers deal with uncertainty and the bewildering swirl of new ideas and opinionation, in an online influence environment that microtargets its audiences to appeal to its cognitive biases.

To this end, Popper provides the method of ‘falsification’, a process through which, when one is confronted with a proposition, it must be subjected to an attempt to disprove it (hence, ‘falsification.’) If the charge can be falsified then they can be dismissed; if it cannot, and the claims are reasonable, the answers are an open question and can be clearly labelled as such.

Embed:

This approach has parallels in reporting: the implication is that clear language can be used to precisely address the status of disinformation circulating in the digital realm; perhaps where journalism needs to up its game is in being able to demonstrate why this is so, in a simple and accessible way, so that the reader can cognitively process the information, without relying simply on someone else’s say so or authority.

To do so requires a deeper commitment to not only chasing exciting headlines but to do the everyday work of fact-checking as a public service. But the real point is to empower citizens to make their own decisions on the basis of sound, verifiable information.

But the principles of this approach extend much further - into an emerging new genre of journalism, which provides excellent opportunities to combat disinformation and the abuses of power through independently verifiable means.

The cognitive challenge and the open source answer

Open source research has been one of the consolations of a period in which the business model for journalism has been disrupted severely by the impact of social media, leading to a decline of print publications, particularly in the important domain of local news. Leading practitioners of open source techniques, such as geolocation and incident analysis through open source material, include projects like Airwars and Forensic Architecture, but its best-known exemplar is represented by Bellingcat, run by Elliot Higgins.

Higgins, who never trained as a journalist, has used digital sleuthing to break stories of global importance, expose lies and embarrass governments. While open source investigations need funding, they do not require vast amounts of money- the sine qua non is technical skill and dedication.

Higgin’s book “We are Bellingcat” chronicles the ways in which a small group of skilled autodidacts, independent researchers and professional journalists can collaborate and score consequential victories for truth over governments attempting to obscure facts, despite the enormous asymmetry in power and resources. What is required is determination, capability (especially in terms of technical literacy and digital research techniques); funding helps to upscale the capacity of journalists practising open source research, but a lack of money does not constrain it fundamentally.

Their work opens the space for open source investigations to use transparent methodologies that can be learned, adopted and independently verified, so that the truth of events can be ascertained, demolishing the lies of corporations, governments and other centres of power.

The Bellingcat model offers a ray of hope in the context of the fractious social media environment and the data-driven economy it feeds. The data process works both ways. By using astute techniques of deriving verifiable information from open sources, Bellingcat have been able to collect and forensically analyse evidence that proves the truth of events about which mountains of falsehoods have accumulated.

A good example of this is the shooting down of the passenger plane MH17 over Ukraine in July 2014 by separatist forces that a Dutch court determined were controlled by Moscow. Bellingcat not only proved that Russian-supplied BUK missiles were used in the assault but were able to track its delivery from Russia to the Donbass region of Ukraine by tracking a convoy through open source material.

They were able to do the same with Russia’s use of nerve agents in Britain, identifying, naming and shaming the perpetrators, even identifying their position within Moscow’s military intelligence service, the GRU. They helped to expose the Russian plot to kill opposition leader Navalny in a similar manner.

This form of journalism is cutting edge for a number of reasons: particularly because it strikes a blow for the possibility of positive knowledge in a sea of disinformation. It represents an antithetical model of informational campaigning to that of the Kremlin; whereas Russia continually seeks to elicit cynical, confused resignation, divert attention, attack the possibility of knowledge concerning events in the world, Bellingcat strives to enhance clarity, de-mystify events and provides its audience with actionable information that can empower them to make informed judgments and decisions, contributing to public discussion. Its methodologies are largely explained and checkable; its effects antidotal.

Moreover, open source investigations of this kind are an example of how this emerging field of journalism can “transform the traditional role of the journalist as “controller” and “gatekeeper” into an enabler of free collaboration,” through “interprofessional” networks of participation, information sharing, sometimes involving crowd-sourced inputs.1

With this in mind, models of media collaboration that enhance democratic security suggest themselves. The point is to engage with the information space proactively and to encourage a space of collaboration that is more representative and engaging of communities, grounded in co-ownership of facts.

Social empowerment

Methodologies like open source investigation or Popper’s ‘falsification’ technique don’t care who you are. They aren’t biased against you because of prejudice or faceless marketing agendas, seeking to appeal to a particular base of consumers, whose data has been collected and are targeted for advertising revenue. They speak for themselves. They are empirical.

Critical rationality and empirical work empower citizens to join in the national conversation, rather than excluding them from it. This is a space which can be expanded further. Likewise, the informal collaborative spirit described at the beginning of this article can be refined further to include people who have technical skills working with their counterparts internationally, to share stories, contextualise local issues in terms of wider events in the world and more generally help to content users construct intellectual self-defence techniques against forms of political and information warfare that seeks to cynically exploit social tensions.

To meet the challenge of the era, as outlined in last month’s post, I propose that small democratic states should work together to seek public funding from governments that are apprised of the threat that disinformation and information warfare pose to their societies. Under a strict code of ethics that guarantees the independence of their coverage, journalists, civil society and other groups can collaborate across borders to pool resources; share knowledge; conduct global investigations and ensure dedicated coverage of issues of shared concern.

Just think, for example, what a boost to reporting in Aotearoa this would provide if a network of professionals could decisively unmask state-backed offensives, corrupt money flows, disinformation, corporate wrong-doing and the like.

In places like the Pacific Island nations in our region, there are brilliant journalists who are forced to navigate the chronic challenges of an underfunded and precarious industry. Secure funding and the absolute gains that can be achieved through meaningful collaborative projects would potentially open the space for hugely important stories, which would otherwise be neglected if attention and funds are not freed up.

This would only be the starting point. The relative success of any such project could be used to fill the gaps left by the decline of local media, to create timely debunking services and shine a media spotlight on stories produced by communities themselves. And inter-professional networks do not have to be limited to journalists: a broader initiative of properly-funded, dynamic, border-crossing research collaborations to combat other urgent social issues and threats would complement the actions of the press.

The point is that the best way to avoid the ‘hacking’ of democracy, as Maschmeyer described it, is to ‘patch’ the system - fix its weaknesses, to renew its purpose creatively, plug its gaps; not discard the whole paradigm.

It may seem like an idealistic pipe-dream to propose such a model. But I believe that there is an appetite for a return of public service journalism that grapples with issues that the pressures of everyday news production have neglected.

Moreover, there is a need to make progress on these issues before the hard choices of a world in crisis begin to bite more severely than they already are. What may seem idealistic and radical now, will later seem necessary and long overdue.

Müller, N. C., Wiik, J., Institutionen för journalistik, medier och kommunikation (JMG), Department of Journalism, Media and Communication (JMG), Göteborgs universitet, Gothenburg University, Samhällsvetenskapliga fakulteten, & Faculty of Social Sciences. (2023;2021;). From gatekeeper to gate-opener: Open-source spaces in investigative journalism. Journalism Practice, 17(2), 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1919543